Saving the Dresden barracks: A story of hope?

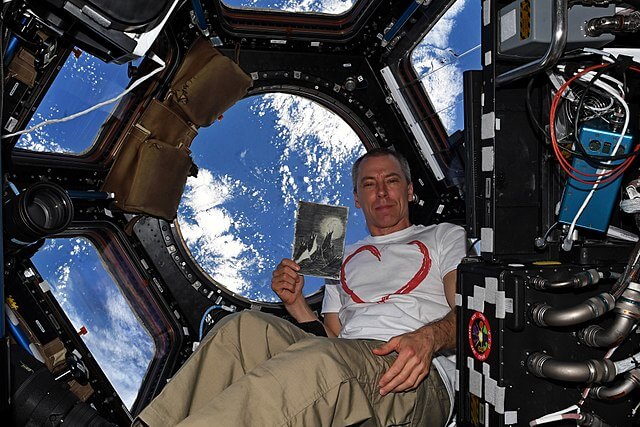

Years before the first astronaut landed on the moon, an exuberant and promising young artist depicted what the view of Earth might look like from up there. Petr Ginz was just 14, and rather than drawing in his bedroom, he was separated from his family and confined to the Terezín ghetto under Nazi rule.

His life would be tragically cut short just two years later when he was deported and murdered at Auschwitz. Decades later, his drawing caught the attention of astronauts and accompanied two missions to outer space. It is stories like this that remind us, as Jan Roubínek, the director of the Terezín Memorial puts it, that “the story of Terezín means more to the international community than ordinary Czech citizens can imagine.” But the site is facing new challenges due to architectural decay and climate change and the future of some of the buildings, which contain important stories, now hangs in the balance.

Terezín, a garrison town from the Austrian and Austro-Hungarian empires, acted as a ghetto for Jews deported from all over Europe during the Nazi era. Initially only the barracks in the town were used to accommodate Jews but by mid-1942, all civilian buildings were used for the ghetto. Thousands of transports brought more than 140,000 Jews to the ghetto in less than four years. The ghetto was used to hold them until they were transported to other camps, including extermination camps.

Of these buildings, the Dresden Barracks were used primarily to house female prisoners with their children. They also served as a place where the Terezín soccer league gathered, making the building not only significant as a place of Holocaust memory but also of the sporting history of the site during that time. Included in the Nazis’ propaganda films, made on site in Terezín, is footage of the soccer league playing outside the Dresden Barracks. These films were meant to paint a picture of a safe and joyful place while hiding the terrible truth of what befell the prisoners at Terezín, where over 35,000 people died as a result of hunger and the atrocious conditions, and many more were transported to their deaths.

After 1945: barracks in decay

The Dresden Barracks were occupied by the Czechoslovak army during the Cold War and have lain abandoned since the ’90s when the city of Terezín took ownership of the barracks. While it architecturally mirrors the Magdeburg Barracks, one of the few well-maintained buildings now part of the Terezín Memorial, a series of storms has reduced this late 18th century building to a state of imminent collapse.

On a recent visit to Terezín, the IHRA Safeguarding Sites Project team noted that much of the roof has blown off the barracks and lies in deep piles of broken wooden beams in the courtyard. Much evidence of victims of the Holocaust in the form of graffiti and personal possessions of those who were once held there has now been lost. The upper stories are no longer safe to explore and serious ceiling cracks and collapses onto the lower floor have now made the building too dangerous to enter without special permission, guidance, and hard hats.

The necessary steps

It has taken decades for Czech society – and the international community – to become aware of the threat facing the Dresden Barracks. Now the barracks are just one rainstorm away from total destruction.

As Jan Roubínek explains, “in terms of funding the rehabilitation of the barracks, the clock is ticking – the Czech government are the ones who are able to help in this urgent situation.” But the question is, does this funding exist and can it be provided in time to save the building?

Last autumn the Czech Ministry of Local Development, Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Culture pledged to save two fortified towns, Terezín and Josefov, from decay with necessary funding. Since that pledge was made, heavy rain has led to the further collapse of the Dresden Barracks, making the situation extremely urgent. Any delay could mean the complete loss of the building.

At the beginning of this year, the three Ministries agreed to go ahead with the initiative to provide emergency funding in the amount of 320 million CZK (ca. 13 million EUR) to temporarily save the roof of the barracks. In July, the Czech government will make the final and crucial decision on whether the funding will indeed go to the restoration of the Dresden Barracks.

The Safeguarding Sites Project team visits the Dresden Barracks in May 2023

Funding the restoration of the barracks will be meaningful if a structured plan is in place. Jan explains that this means looking at the rehabilitation of the building in three steps: first, further decay of the building needs to be prevented so that the building does not collapse; then, the full restoration of the building needs to be realized; finally, the future of the building needs to be considered. Jan sees the potential for international organizations to collaborate on this final step and bring their own ideas for how to use the building meaningfully in the future.

The national initiative to provide funding to the Dresden Barracks would provide funding for the first two steps, but the third step goes beyond funding and would require the involvement of a third party. Jan believes that one step cannot exist without the others and that without a future vision for the barracks, restoration would be less meaningful. “If you have a 250-year-old building without a vision for the future, in 20 or 30 years the building will begin to deteriorate again.”

Preserving Terezín’s past while securing its future

The town of Terezín has a population of around 2,000 but it can accommodate much more. With Prague and the German state of Saxony within short driving distances, Jan believes this town has the potential to be much more than it is today. The appropriate reuse of buildings like the Dresden Barracks could attract the young professionals needed to not only revitalize the town but also to bring the story of Terezín to new generations – securing remembrance while also ensuring a prosperous future for the town. The proposed funding, along with international cooperation, has real potential to make this possible.

Jan Roubínek hopes that the building will be restored and that part of it will be appropriately reused to commemorate the history of the building while the other part is used for the local community. As for Jan’s vision for the future of the Dresden Barracks, he says he “can only speak as a good neighbor and citizen of Terezín, as this decision lies with the local municipality. For me, Terezín should give the world a vision of hope. Terezín is not only about death and the Second World War. The stories of prisoners’ lives, and who they were before they were imprisoned, is one that deserves to be told – international collaboration on this in the buildings that are now under threat of collapse could invigorate those stories as well as the town itself.”

Astronaut Andrew Feustel holds a copy of “Moon Landscape” by Petr Ginz

Hope perseveres

After young Petr Ginz’s drawing made it all the way to outer space and back with Andrew Feustel, the US astronaut visited Terezín, bringing with him young students to learn about Terezín’s history. Petr’s artwork, like the artwork, music, and sporting activities carried out by many prisoners of Terezín, acted as a glimmer of hope and creativity in the darkest chapter of humanity. Jan Roubínek believes that this hope can attract younger generations to Terezín for years to come, just as it attracted those students accompanying Andrew Feustel, and in doing so secure the future of remembrance. Therefore, the buildings, when restored, do not need to be directly related to the Holocaust or the war. They could instead serve as a creative or recreational space and, in doing so, celebrate the legacy of those who were interned in Terezín, who spent their last days creating art that still captures our imaginations and dreamed of a world where these activities could be carried out in freedom.

Optimism remains that emergency funding will be provided to rehabilitate the building as a space of hope in memory of Petr Ginz and all those who dared to dream of a better world. Saving the Dresden Barracks not only saves the history of Terezín; it helps the town to reimagine itself as a place of hope for generations to come.

Sign up to our newsletter to

receive the latest updates

By signing up to the IHRA newsletter, you agree to our Privacy Policy