The extraordinary journeys of ordinary objects

What socks are you wearing? White, or black, or mismatched? Maybe no socks at all, depending on where you are in the world. Socks are a part of our everyday life, so when you look at photos of these hand-knitted cotton socks which used to belong to Eda de Botton, the main thing you may notice is how ordinary they are. Despite not looking so different from ours, though, these socks were knitted in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

They are currently in the Jewish Museum of Greece, in Athens, where the everyday person, certainly a person who doesn’t live in Greece, would never get a chance to see them. But thanks to the IHRA-funded website Ordinary Objects, Extraordinary Journeys, they’re accessible to anyone who wants to see them. Anybody can have a deep look at the socks, imagining the weave and the texture in their hands, as they learn about the life of Eda de Botton and the terrible journey that led her to knit them.

Eda knitted these socks for her daughter, Reina, from whom she’d been separated. Seeing as yarn was a rare commodity in the ghetto, Eda would have had to make hard choices to source it, possibly by swapping her already-limited food allowance.

This pair of socks is one of four items presented on the website, each one retracing the steps of a person whose life was irreversibly altered during the Holocaust, and exploring their story through the possessions that meant the most to them. The website, which was launched last year by the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust and the National Holocaust Centre and Museum in the UK, in collaboration with the Jewish Museum of Greece, is an attempt to maintain stories of the Holocaust as the survivor generation passes.

In their absence, it’s both crucial and urgent to maintain these stories, and to find ways of keeping them alive for future generations. Dr Rachel Century, Director of Public Engagement and Deputy Chief Executive at the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust, says that choosing to highlight artefacts like this is an important strategy to “future-proof” Holocaust education, “because when the survivors leave us, we’ll still have the artefacts.”

Working with an international partner is a requirement of an IHRA grant, and the collaboration with the Jewish Museum in Greece, says Rachel, led to a much richer outcome. After all, working together and collaborating is a crucial part of the field. “We’ve all got the same common goals in terms of education and commemoration. We also have different resources — let’s use them together.” Working in this way meant that they were able to show these objects to people who would have never heard these stories. British audiences wouldn’t know much about the experience of Greek Jews in the Holocaust, and Greek audiences wouldn’t necessarily know much about the Kindertransport – children who came to Britain before the Second World War broke out.

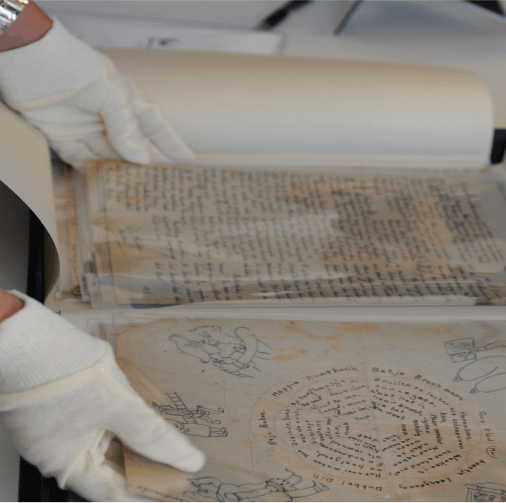

Another extraordinary object highlighted is a diary written by Julius Feldman, which was found hidden in the wall at Płaszów concentration camp in Poland after the war. Julius himself is believed to have been murdered there, at 19 years old. Rachel says, “We didn’t just want to show survival because after all, survival was an anomaly. More people were murdered than survived.” Julius’ diary ends mid-sentence on 11 April 1943. This sudden end point of Julius’ diary leads us to consider all the potential lives, what they would have been. “What would Julius have gone on to do?”, Rachel wonders.

There’s always an element of mystery to the objects that remain. Another collection of objects on the website comes from Julie Weiss, who fled Austria after the German invasion and made her way to London. She was pregnant and alone, and we know little of the details of her journey. But what we do know is what she brought with her — her most treasured objects, linking to her family and identity, in an attempt to bridge the many kilometres between her old life and an unknowable future.

Julie’s father ran the local chess club in Graz. One of the items she brought with her was a chess set, and a collection of medals she’d won from local chess tournaments. She also brought a mezuzah, a small parchment scroll upon which the Hebrew words of the Shema are handwritten by a scribe. Mezuzahs are traditionally attached to doorposts, telling the world that this is a Jewish home, and reminding those who live there of their religion and heritage. Despite the fear that Julie surely felt, carrying objects with clearly Jewish origins, she must have felt that this connection to her past was worth the risk. We don’t know if she ever saw her original family again, but she arrived safely, and gave birth to a son, David, in 1939. Eighty years later, after they had both passed, a friend of the family donated these objects to the museum.

Creating such detailed content is of course tricky, and many different hands are required to take these photos of such delicate items, and to find the throughlines in dry documents and archives. It required close cooperation between the project partners, and even after the best coordination, there are often unexpected turns of events. For the project team, one of the most disappointing was that a beautifully-planned launch event had to be quickly taken online at the last minute due to a rail strike.

But despite setbacks, the website has found many enthusiastic users. In addition to the website itself, the team also created supplementary educational materials, helping teachers to use these stories in their teaching. They’ve been used in teacher training, as well as in a hospital school, where children who aren’t able to access their usual schooling receive education.

The story of Eda and Reina is an anomaly in the historical context: they both survived, and were later reunited. Of course, when they met again decades later, Reina was an adult, and the socks didn’t fit. But although these socks were never worn, they allow us to access a story, a labour of love that it’s vital we preserve.

The Ordinary Objects; Extraordinary Journeys website can be found at ooej.org

The IHRA’s 2023 grant application programme is open until 29 September. For more information and to apply: https://www.holocaustremembrance.com/resources/funding

Sign up to our newsletter to

receive the latest updates

By signing up to the IHRA newsletter, you agree to our Privacy Policy