Why are networks important for archival research?

On this page

- Why are networks important for archival research and for open access?

- What benefits do these networks and connections offer that otherwise the Monitoring Access to Holocaust Collections Project would be missing?

- What has the project group learned through these partnerships?

- What challenges have you encountered through this process? How have you overcome them?

- Why is the IHRA in the position to have a project with such networks and connections?

The Monitoring Access to Holocaust Collections IHRA Project, which helps further open access to Holocaust-related materials, has made building partnerships and strengthening networks central to its approach. We spoke with Dr. Veerle Vanden Daelen, member of the IHRA’s Belgian delegation and the Project Chair, about why networks are so important and how the IHRA Project has contributed to and benefited from them.

Why are networks important for archival research and for open access?

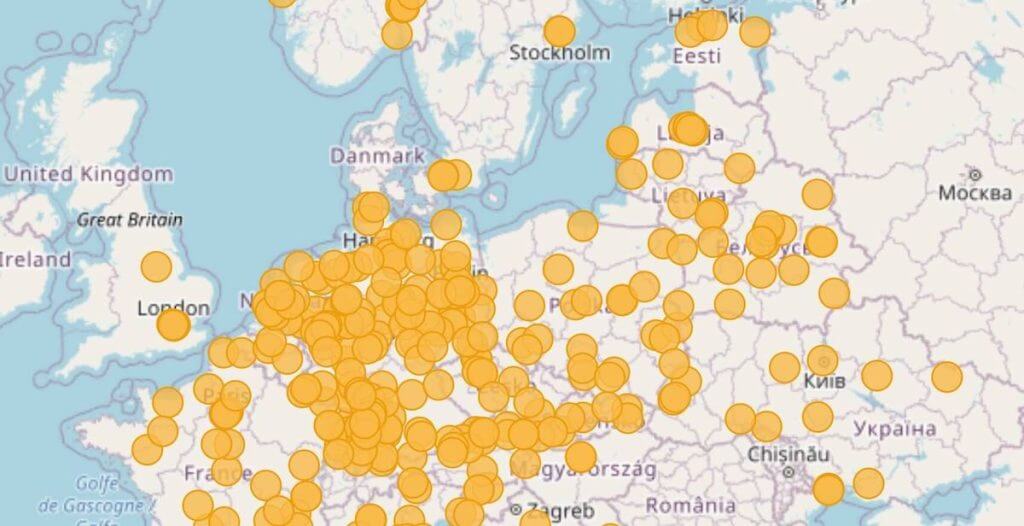

Holocaust-related documents are spread over archives, depositories, and continents. They are open-ended both geographically and in their time frame. When dealing with the archival record of the Holocaust, there is no institution that holds all records or that has the expertise on all the sources. Therefore, networks to support all efforts to adequately preserve, describe and open up the records on the Holocaust are of crucial importance.

It’s like building a huge puzzle when each piece is held by a different person or entity. Only by networking and working together can the puzzle become whole and the picture clear. Networks help connect the actors who hold pieces of this puzzle; they create communities. And these communities can then work together to share information and good practices. The more the sources can be made accessible, the stronger the communities can become, and vice versa.

“It’s like building a huge puzzle when each piece is held by a different person or entity. Only by networking and working together can the puzzle become whole and the picture clear.“

What benefits do these networks and connections offer that otherwise the Monitoring Access to Holocaust Collections Project would be missing?

The networks do not only strengthen exchange of knowledge and cooperation – which can also result in greater motivation and commitment among all those involved – they also help with exchange of good practices and possibilities to learn from each other. There is simply no way to preserve and open all archival sources on the Holocaust “solo” or in a void.

The sheer amount of sources, the multitude of languages and scripts they are written in, preserved across the globe in various institutions following local laws and customs demands contact between a multitude of actors, both on expert and on legal and political levels. Providing networks and fora to facilitate this is of crucial importance to ensuring adequate preservation and access to sources on the Holocaust.

What has the project group learned through these partnerships?

We have learned about the richness of the existing networks, each of which addresses specific institutions (such as national archives) or topics (such as bringing together descriptions of archival sources on the Holocaust into one portal). We also see that these networks take an interest in the IHRA approaching them with the specific concern of access to Holocaust sources. This joint commitment is outlined in article 7 of the Stockholm Declaration [“We will take all necessary steps to facilitate the opening of archives in order to ensure that all documents bearing on the Holocaust are available to researchers.”], as well as in article 10 of the 2020 IHRA Ministerial Declaration [“Underline the importance of identifying, preserving, and making available archival material, testimonies and authentic sites for educational purposes, commemoration and research.”].

These contacts have also emphasized the need to bridge the gap between the political, juridical and expert (archivist/researcher) levels concerning the topic of access to Holocaust sources. It is encouraging for the IHRA to keep on working via this method to strengthen this approach.

What challenges have you encountered through this process? How have you overcome them?

The pandemic, needless to say, has challenged all of us in our ways of working. It is one of the paradoxes of virtual teams that they are the most successful when they also meet in person. For those networks that already existed pre-COVID, their pre-COVID meetings allowed them to continue their work via telecommunication, albeit in a different way. Within the IHRA team, many participants had met (and often already worked together) in person before the pandemic, thanks to the IHRA Plenary meetings. The same was true for the external networks we met and cooperated with. It all did require some flexibility and creativity though, and certain activities have been postponed.

At the same time, the closure of so many institutions and the introduction of travel restrictions during the pandemic have made it terribly difficult for researchers (including our own project’s researcher) to visit the locations preserving the sources, hence providing even more of a reason to plead for access to sources in as open a way as possible.

The latter, though, immediately highlights one of the challenges that comes with access to archives, which is ensuring that this access respects all GDPR legislation and is provided with sufficient context so that those consulting the sources have all the information they otherwise would have received “in situ.”

Why is the IHRA in the position to have a project with such networks and connections?

Because of the unique constellation of the IHRA, with both political representation and experts on research, education and commemoration, the IHRA can play a role in strengthening networks and connections both internally and externally. It serves as a much-needed intermediary, that brings people, organizations and (in)formal networks together and, in this way, strives to implement the Stockholm Declaration and the 2020 Ministerial Declaration.

In the case of this project, by focusing on article 7 of the Stockholm Declaration and article 10 of the Ministerial Declaration, the IHRA steps into a discussion on access to archives, GDPR, digital preservation and opening of archival sources, with a concrete mission and topic: saving the record of the Holocaust and ensuring that all that can be done to allow and support Holocaust research, education and commemoration via access to archives is indeed done. The project brings the IHRA into new networks and sparks new discussions. The fact that this project deals with such a concrete example and that so many wish to support this endeavor leads to real change and implementation.

Dr. Veerle Vanden Daelen is the Deputy director and Director of Collections & Research at the Kazerne Dossin: Memorial, Museum and Research Centre on the Holocaust and Human Rights, Belgium. She received her PhD from the University of Antwerp on “The return of Jews and reconstruction of their life in Antwerp after the Second World War (1944-1960).” She has taken part in fellowships at the University of Michigan (Frankel Institute for Advanced Judaic Studies) and at the University of Pennsylvania (Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies). The coordinator of the work package “Data Identification and Integration” for the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI), Dr. Vanden Daelen is also affiliated with the University of Antwerp, where she has taught “Migration History,” “Jewish History” and other classes and where she organizes the annual “Contact Day Jewish Studies in the Low Countries.”

Focus area

Holocaust archives and research

We are helping victims, survivors, and their descendants to reclaim their histories and identities.

Find out more

Sign up to our newsletter to

receive the latest updates

By signing up to the IHRA newsletter, you agree to our Privacy Policy