Why do we need to safeguard sites?

by Safeguarding Sites Project Chair Gilly Carr

The answer to the question of why we need to safeguard sites is something that we might feel instinctively, as something self-evident and obvious. These are sites of pilgrimage for many and a place to mourn victims. They are also places of education and remembrance, places that teach us about inhumanity. They are crime scenes: places where archaeologists are today able to reveal evidence of genocide, crimes against humanity, and even just the possessions of former victims. And yet former internment, labor, concentration and death camps, not to mention prisons, ghettos and killing sites, have not remained perfectly preserved, like Pompeii, since 1945. They are not untouched and pristine.

All sites face a variety of serious challenges today

Of the original 44,000 sites of the Holocaust that the USHMM calculated were run by the Nazis and their allies, only a fraction of these still stand today. Many were torn down after the war and have long since been built over, with nothing remaining. Others were reused after the war, most especially the prisons, some of which are even still in use today. Of those sites which today are memorials, every single one faces challenges or threats. This bears repeating. There is not a single Holocaust site or site of the genocide of the Roma which is properly and entirely safeguarded.

While one of the most pressing challenges today is financial, triggered by the pandemic and a loss of physical audiences, a multitude of other problems plague these sites right now. Before the pandemic, many sites had the opposite problem: wear and tear caused by too many visitors was a real concern for site managers.

Of those sites which today are memorials, every single one faces challenges or threats. This bears repeating. There is not a single Holocaust site or site of the genocide of the Roma which is properly and entirely safeguarded.

All authentic sites still standing are now over 75 years old. This in itself means that problems of natural decay caused by damp, insects and vermin are a strong enemy. Most camp sites were made predominantly of wood and were not constructed to last for decades. Other sites face deliberate destruction or damage through vandalism, extremist action or even warfare.

Some sites are not protected by heritage legislation. This can leave them vulnerable to demolition or reuse. If they are situated on private land, the remains of unprotected sites can, in some countries, be dug up and the land reused for other purposes. Landowners may also have the power to prevent access. Even where sites are not destroyed, insensitive restoration, additions or reuse can impact the authenticity of the site. Some sites with a history of Holocaust or genocide have been inappropriately reused as shopping centers, or disrespectfully turned into sausage museums or pig farms, to give two notable examples. Although reuse which prioritizes remembrance or education is best, it is vital that sites of the Holocaust acknowledge their previous history, and that reuse prioritizes remembrance and education as much as possible.

Safeguarding sites is critical to countering distortion

Paying respect to the sites and their victims means acknowledging and remembering all victim groups. Failure to recognize certain groups and their narratives risks distorting the historical record. Sometimes this distortion can even be the deliberate act of political parties or governments, who may also seek to (mis)appropriate certain histories to suit their own agendas. At a time of rising political extremism, this is becoming an increasing concern.

As these sites are evidence of a crime, restoration, heritage protection or excavation efforts are often not supported. The only trace of some camps is now underneath the soil. This enables denial to flourish.

Engaging local communities in safeguarding sites while working closely with experts is the next step

Local communities living nearby can also be a force for good or ill, preventing excavation, blocking planning applications for memorials, or simply not wanting their town to be known primarily for its dark history. Yet, with education and support, those same communities can also become proud and supportive champions of their local history. Working together with site managers, historians and activists, community groups can make the difference between safeguarding a site for the future or silencing it forever.

The IHRA’s Safeguarding Sites project works to identify the challenges facing authentic Holocaust sites and sites of genocide of the Roma today. Through working with sites facing those challenges, the team is producing best practice guidelines to help safeguard all sites.

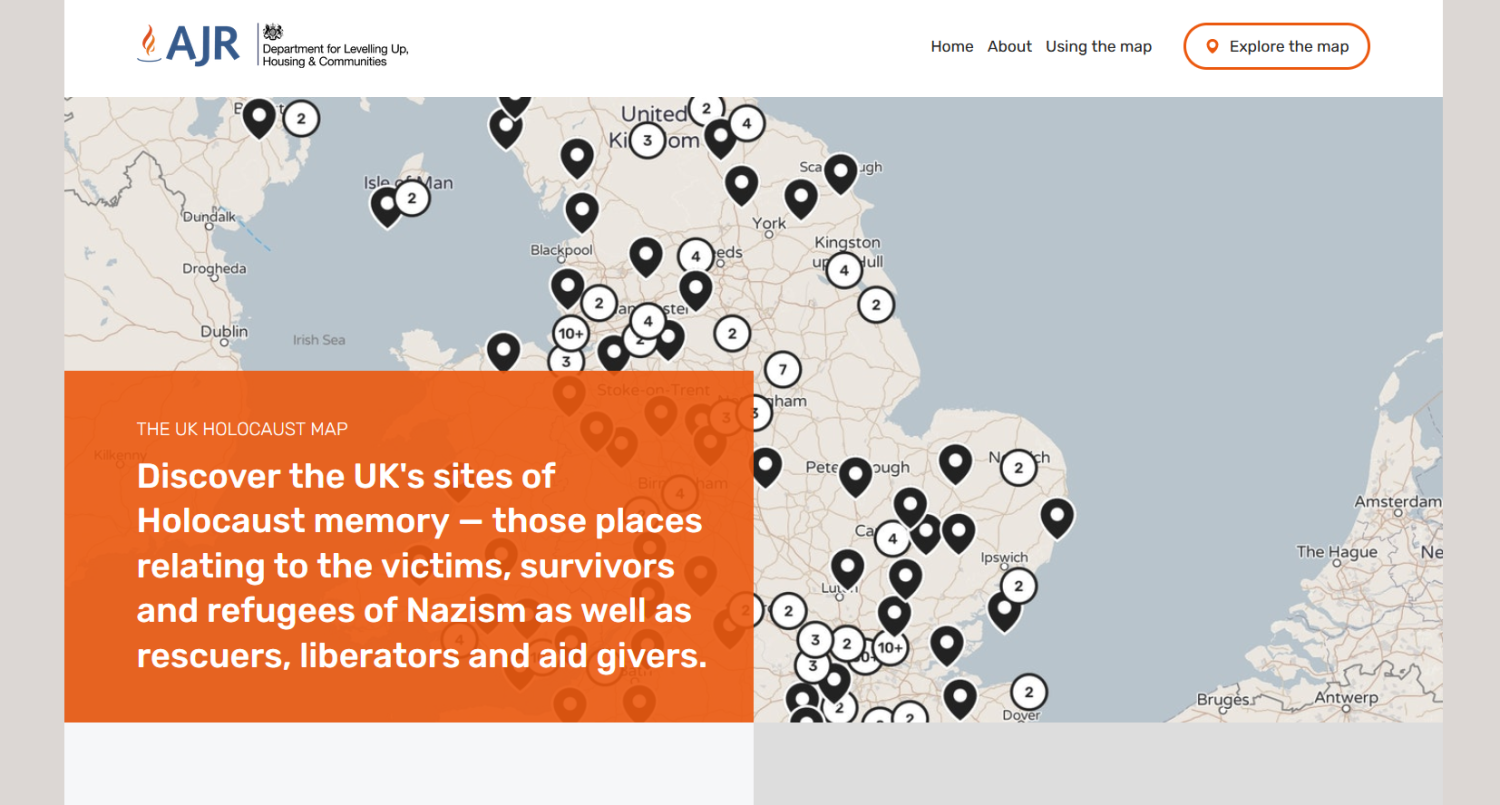

Highlighting Holocaust heritage

Credit: University of Cambridge, Public Engagement and the Cambridge Creative Encounters Project

Why We Safeguard Sites

On occasion of the public launch of the IHRA Charter around International Holocaust Remembrance Day, we asked people who work at sites what safeguarding means to them.

Hear what they had to say.

Focus area

Sites of the Holocaust and the genocide of the Roma

We work with memorials and museums and help safeguard the places where the Holocaust happened.

Find out more

Sign up to our newsletter to

receive the latest updates

By signing up to the IHRA newsletter, you agree to our Privacy Policy