“I said, ‘Auf Wiedersehen’” exhibition shows 85 years of the Kindertransport to Great Britain

In 1939, Ferdinand Brann gave his daughter Ursula a prayer book before she departed from Germany on a Kindertransport to England. On its first page, he had written ten guiding principles for her to begin her new life with. The principles offered Ursula guidance on remaining hopeful as she began her new life far from home. They also advised her to never forget Germany, her family’s home.

Ferdinand never saw his daughter again. Ursula’s parents and older sister did not escape Nazi persecution and were deported to Auschwitz and murdered. The Kindertransport saved Ursula’s life.

The Kindertransport was one of the most significant efforts to protect Jewish children from persecution. In response to the antisemitic violence of the November pogroms of 1938, the British government agreed to a rescue operation initiated by Jewish and other aid organizations. From December 1938 to September 1939, more than 10,000 mostly Jewish children from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Poland were brought to Great Britain.

The children were placed in English foster families, residential homes, and schools. They began life in a new country, with a new language, and in a foreign environment. As the Second World War began, communication between the children and their parents became difficult. Many waited years before learning of their parents’ fate, most of whom struggled to escape their home countries. Most of them did not survive the Holocaust.

The Kindertransport children were often the only Holocaust survivors in their families.

The letters exchanged between Ursula and her parents are featured in the exhibition “I said, ‘Auf Wiedersehen’ – 85 years since the Kindertransport to Britain.” Commissioned by the Berthold Leibinger Stiftung and curated by Ruth Ur, the Director of the German Friends of Yad Vashem, the exhibition commemorates the rescue of over 10,000 children from Nazi-controlled territories to Great Britain between 1938 and 1939. It presents selected letters from five Jewish families, reflecting their hopes of reunion and their fears of permanent separation.

The exhibition is a significant step forward in understanding the Kindertransport experience and the suffering endured by Jewish families during the Holocaust.

Abschied: The story of Ursula Brann

In 2007, Ursula recited Ferdinand’s ten guiding principles from her prayer book during a three-hour interview with Dr. Bea Lewkowicz from the AJR Refugee Voices Archive. When asked to say her name at the beginning of the interview, she first pronounced it “Oor-sula” in the German way, before switching to “Er-sula” in English. Ursula embodied the strong sense of identity expressed in her father’s principles.

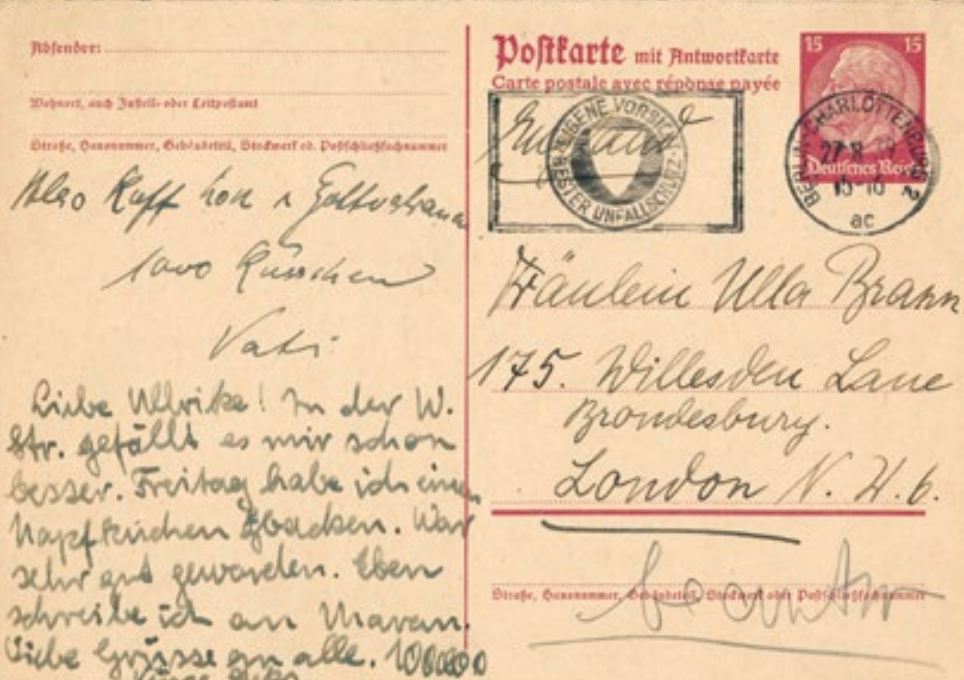

Postcard to Ursula Brann from her parents Ferdinand and Rose-Marie Brann and her sister Stefanie Klara Brann, 27 August 1939

After Ursula’s death in 2015, her prayer book went missing. In the search for the original book, Ruth Ur discovered that Ursula’s two sons had inherited a set of boxes filled with photographs and letters from her parents, sister, and friends. These letters reflect her family’s love for her and their efforts to shield her from the difficulties they faced in Germany. Her mother, Rose-Marie, wrote about Sunday outings, memories that sharply contrasted with the increasingly threatening situation at home.

Although the prayer book was not found, Ursula had carefully preserved each letter she received. The boxes she left to her sons are believed to contain the largest collection of letters related to the Kindertransport.

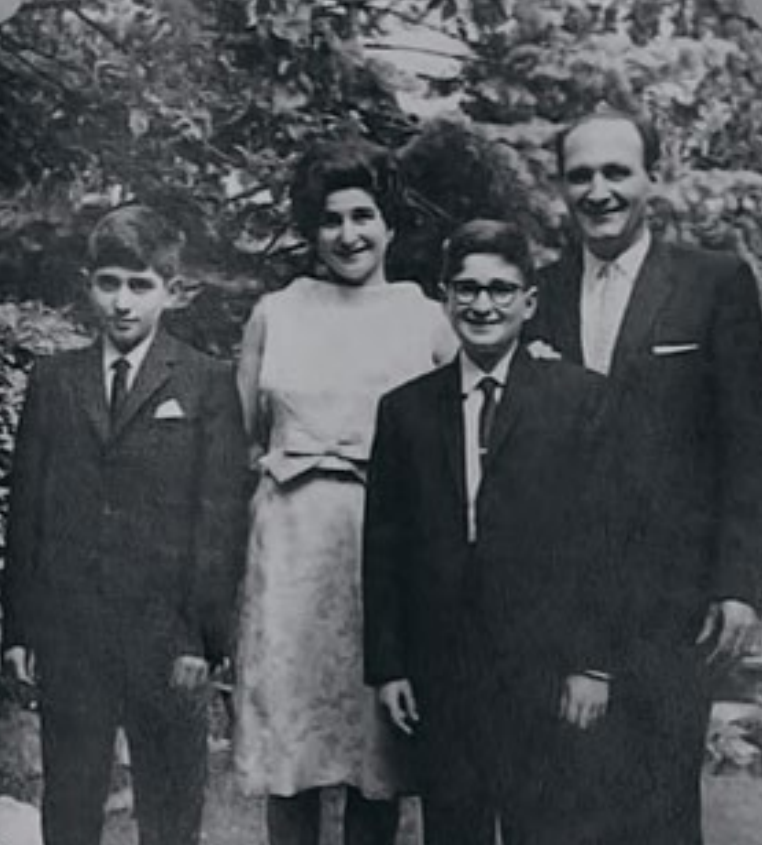

Ursula with her husband Harry Gilbert and their two sons Raymond and Stephen, year unknown

Neues Zuhause: The story of Ilse Majer

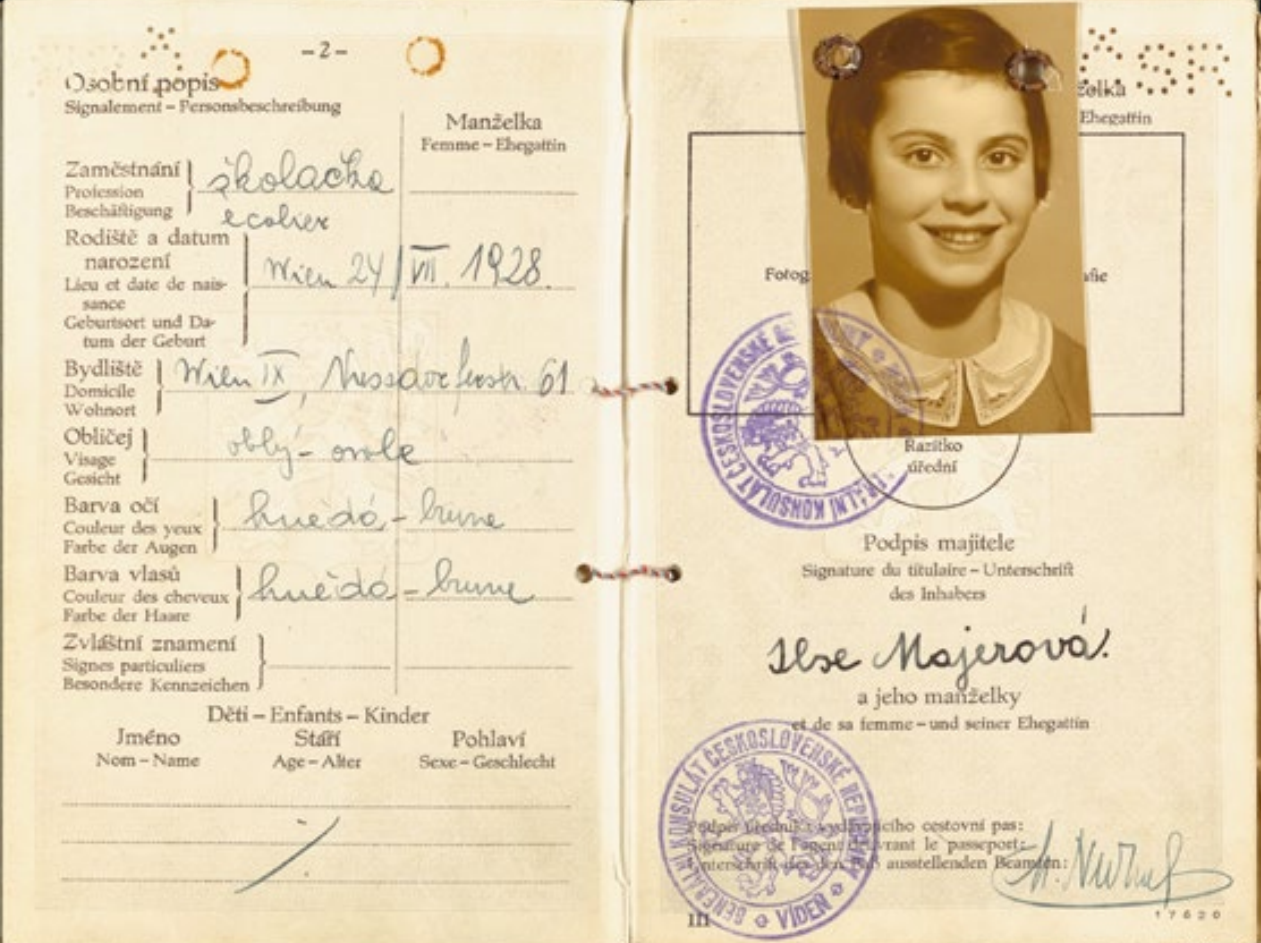

Ilse Majer was ten years old when she was sent from Vienna to England on a Kindertransport in 1939. She was taken in by Lady Howard-Stepney and her family, beginning a new life. In a letter to her parents in July 1939, she included a drawing of her new nursery and often spoke about all the things she would show them once they joined her in England. Ilse was never reunited with them.

Ilse's Czech passport, issued on 18 January 1939

Ilse’s foster family wrote to Lilly and Berthold Majer, expressing hope that they would receive their permits and join Ilse in England. Their letters provide insight into Ilse’s world and show that she was too young to fully understand her own situation.

Like many other children rescued by the Kindertransport, Ilse lost her parents during the Holocaust. In June 1942, Lilly and Berthold Majer were transported to the ghetto Izbica in Poland and later murdered.

Ilse remained in England until her death in 2003.

15-year-old Ilse, London, around 1944

Entfremdung: The story of Heinz Lichwitz

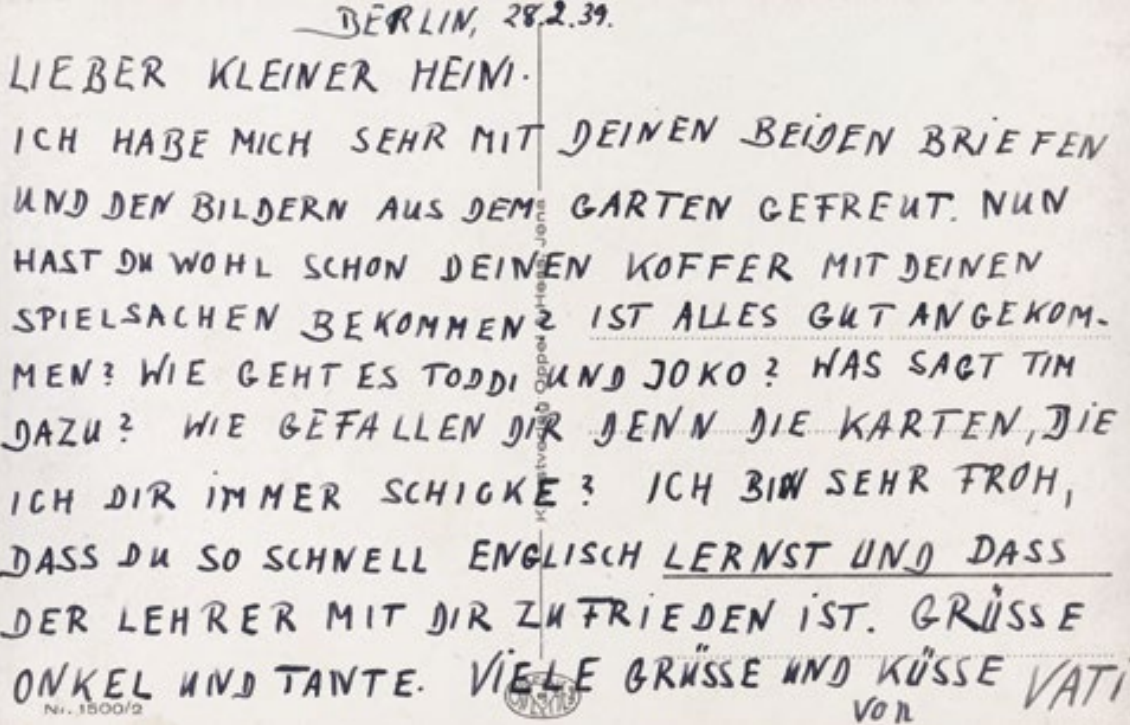

Max Lichtwitz regularly wrote to his son, Heinz Lichwitz, sending postcards adorned with vibrant landscapes and animals – images that starkly contrasted with the grim reality of their separation and the war.

Heinz was raised by his father and grandmother after his mother’s death in 1937. In February 1939, he escaped on a Kindertransport from Germany to England, where Morris and Winnie Foner gave him a home in Wales. He was six years old. He adopted the name Henry Foner and almost entirely lost his mother tongue within months

In the postcards, Max wrote about Henry’s toys and his hopes for his son’s well-being. The postcards also reflect Max’s growing fear that he might never see Henry again. In December 1942, Max Lichtwitz was deported to Auschwitz and murdered.

Henry Foner, now 90 years old, lives in Jerusalem.

Heinz in the arms of his father Max Lichtwitz, around 1933

Sehnsucht: The story of Gerda Stein

“At exactly twelve o’clock midday, we will all look at the sun at the same time from Prague, London, and Lemberg, and hope that one day we can be together, hand in hand.”

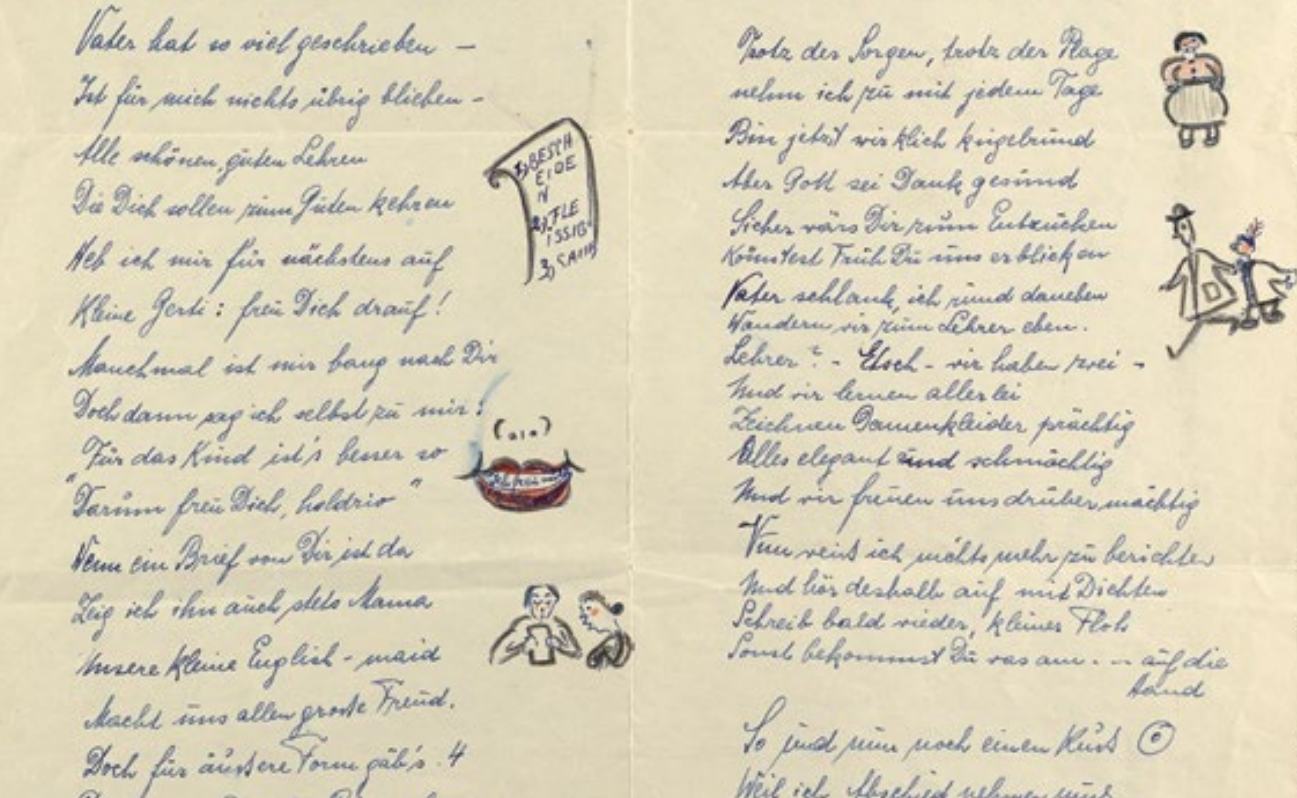

Gerda received this message from her father for her birthday. He sent her a detailed letter with a colorful, hand-drawn illustration of herself, her father, and her mother, each in different countries, all looking at a bright yellow sun. In another letter, her mother wrote her a poem with miniature illustrations next to its verses, bringing her happiness and hope.

Gerda fled on a Kindertransport from Prague to England in March 1939. She was 11 years old.

She lived with Trevor Chadwick, a Kindertransport organizer who rescued many other children from former Czechoslovakia. The letters she received, including a colorful postcard, reflected her parents’ deep longing for her.

Despite their efforts to reunite with their daughter, Arnold and Erna Stein could not bring their family back together. Neither of them survived the Holocaust.

Gerda died in 2021. She was a well-known poet.

Gerda and her father Arnold, year unknown

Ungewissheit: The story of Hannah Kuhn

In 2023, Ann Kirk sat with Ruth Ur in her London home, looking at a photograph of herself from 1934. She was six years old in the picture.

Hannah as a 6-year-old, around 1934. This is the photo Ann and Ruth were looking at (mentioned above)

Born in 1928 as Hannah Kuhn, she fled from Germany to England on a Kindertransport, shortly before the start of the war, as Nazi persecution of Jewish communities intensified. Her parents, Herta and Franz Kuhn, remained behind. In London, Hannah was taken in by two Jewish sisters and began a new life as Ann.

Ann’s parents learned about her childhood through letters exchanged with her foster mothers during the war. As the war progressed, the letters became sparse, often arriving after months of silence. Eventually, they were reduced to brief and rare messages relayed through the British and German Red Cross.

In February 1943, Ann received one final telegram from her father, informing her about her mother’s deportation and expressing his hope to reunite with his family after the war. A few weeks later, he too was deported. Both Franz and Herta Kuhn were murdered at Auschwitz.

The travel document with which Hannah left Germany, 1938

The Kindertransport saved the lives of 10,000 mostly Jewish children. It reflects both the resilience and the profound loss of the children and their families.